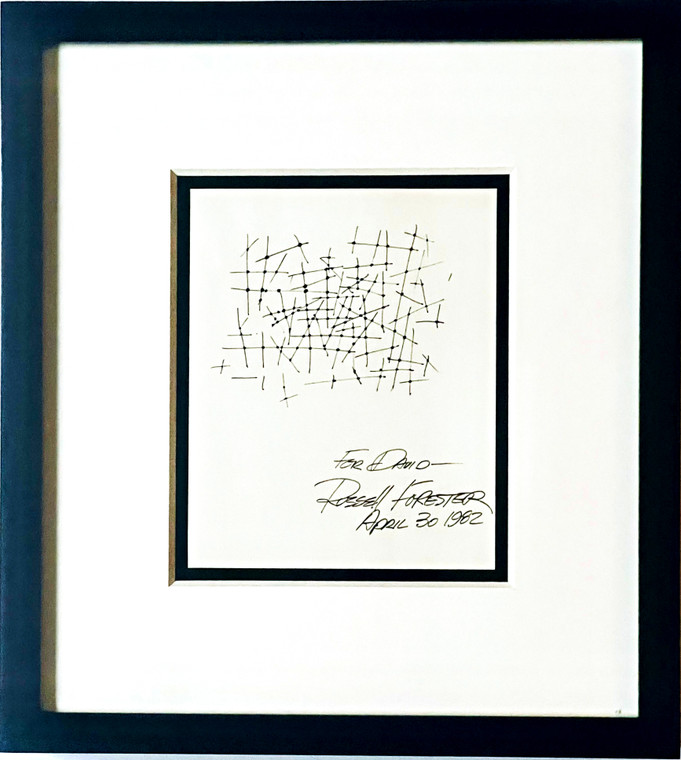

California Architect and Artist Russell Forester (1920-2002), Original Drawing, Uniquely signed & dedicated to art professor Dr. David Luisi, 1982, Framed

Russell ForesterCONTACT GALLERY FOR PRICE

Unique original hand signed, dated and personally dedicated drawing by the renowned American (West Coast) architect and artist Russell Forester (1920-2002). The work is elegantly floated and professionally framed.

This special piece came from the private collection of Dr. David Luisi of San Diego, and is accomanied by a copy of a poignant letter from Professor Luisi certifying the work's authenticity and explaining how he acquired it; After describing how he spent his youth visiting art museums. Professor Luisi writes, "Even though I lacked the money to purchase art from famous artists, then at least the slightest contact with them would...allow me to share some of their greatness. With this fantasy in mind I wrote to dozens of artists asking, if they would please send me an autograph... My pleas must have sounded so desperate that they responded not only with autographs but sometimes with small examples of their art, letters and other art memorabilia. Now that I am elderly and the stresses of those years have passed, I am deeply grateful for the kindness of these artists and the psychological lifelines they extended when I needed it most."

The Luisi collection was one of the very best of its kind ever to come to market.

This original 1982 drawing remained in Dr. Luisi's private collection for 30 years. Luisi only sold it because of his advanced age. The provenance is impeccable as it was gifted and dedicated by the artist directly to David Luisi.

A rare find! Framed, the work measures 9.5 inches (horizontal) by 10.5 inches. (vertical). The sheet itself measures 6 inches by 7.5 inches.

Russels Isley Forester

1920-2022

Born in 1920 in Salmon, Idaho, at age five Russell Forester moved to La Jolla with his younger brother and mother – who notably served as librarian at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography where a number of the architect’s clients would later conduct their research. Russell’s father, an architect, had abandoned the family.

Russell graduated from La Jolla High School in 1938 and later served in the Army Corps of Engineers (1943-46), where he began his architectural career as a draftsman alongside Lloyd Ruocco. Together, with other budding designers, the team designed ‘replacement depots’ while much of his free time away from the drafting table was devoted to drawing.

Russell’s first wife, Eleanor, was born on December 11, 1924, to Eva Lucille Puckett and George Albert Hedenberg. Eleanor moved to San Diego with her mother and stepfather, Kenneth J. Darrell, in 1939. After graduating from Hoover High School she worked in a drafting position for Concrete Shipyards designing barges for the War effort. At Concrete Shipyards, she met Russell and they immediately hit it off, forcing the head draftsman, Lloyd Ruocco, to move their desks apart since Russell spent too much time turning around to talk to her. Eleanor and Russell married on April 13, 1946, in La Jolla.

Mr. Forester opened his first office, at 7438 Cuvier Avenue, in 1948, as a freelance architectural designer. At this early stage of his career, he designed four houses: for Lloyd and Betty Russell at 348 Vista de la Playa, his own home at 724 Rushville, a house for Ruth Dailey on Ludington Place and the Cromwell's home on Vista de la Playa.

Inspired by- and at the urging of Ruocco, not to mention financing from the GI Bill, Russell sought out formal architectural studies. Between 1950-1951 Russell attended the Institute of Design (later IIT) in Chicago where Mies Van Der Rohe and others were spreading the International Style gospel. Founded as the ‘New Bauhaus’ in 1937 by Bauhaus educator László Moholy-Nagy, by the time Russell arrived Serge Chermayeff was serving as its director. Russell later recollected that his foundation course focused on perception, space, light, proportion and texture. Eleanor and Russell returned to San Diego when his mother became ill.

Russell’s formal studies, in Chicago, had a major impact on the development of his approach. While his early works, of 1948-49, were fairly traditional, Russell's work following his time in Chicago were boldly 'contemporary'. His home designs in Scripps Estates Associates, near La Jolla Shores and elsewhere in La Jolla exemplify his new approaches in wood and glass.

Eleanor and Russell built three family homes together before they divorced after 20 years of marriage: their first house at 724 Rushville Street in April 1948; their 2nd house on Hillside Drive in 1952; and a spec house in the upper Shores area in the early 1960s.

Eleanor was an accomplished and successful interior designer. Her company, Eleanor Forester Interiors, based in downtown La Jolla, focused on both commercial and residential projects. She designed dormitory rooms for UC San Diego, a string of banks, homes for Robert Peterson, Harle Montgomery, Joan Holter, William Karatz, and the Sampson, Mayne, Muzzy, Fayman, Kimmell, and the Marston families, among others. Eleanor also did residential work in San Francisco, Hawaii, Mexico, New York, and Montana. Asked to write a monthly column for San Diego Magazine by editor Ed Self, she wrote the "La Jollans are Talking About" column in the early 1960s.

Russell opened his first office at the time his Rushville Street home was “chosen by a distinguished jury as one of the top residences in the United States for Progressive Architecture magazine.” His second home at 7595 Hillside Drive was “displayed in an international architecture exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1952.” Eleanor and Russell spent a year in Spain in 1955-56 while he “worked for a firm of engineers and architects on U.S. bases in Spain” as designer and supervising architect. After two years, Russell returned stateside “as a designer on the Los Angeles airport for the firm Pereira and Luckman.” By the time he obtained his architectural license, in 1960, Russell had already completed a wealth of modernist structures.

Russell was among the first wave of San Diego architects to emphasize the benefits of ‘steel and glass modernism’, championed elsewhere by the likes of Mies Van Der Rohe, to commercial and residential clients here. From his La Jolla practice, Mr. Forester enjoyed a number of commissions by local art patrons Lynn and Danah Fayman as well as restaurateurs like Bob Peterson. For Foodmaker’s CEO, Peterson, Russell pushed Mieisian modernism into pop culture by designing the first Jack in the Box restaurant in 1951. As Jack in the Box’s “machines for dispensing food” grew to well over 200 drive-thru restaurants inside 20 years, Peterson would also have Russell design the Family Tree, a more elegant setting for dining in San Diego, as well as his personal residence.

Russell Forester defined architecture as problem solving. From his Philosophy of Practice, he wrote, “We believe that good architecture grows out of a thoughtful, direct and imaginative approach to each owner’s individual problem. Our unique systems approach to the total project from the feasibility studies through design and finished construction gives us an economic and functional solution. Our understanding of the complexity of each client’s problems and the professional and artful solution to his needs is our concern. In our practice all functions (architecture, feasibility studies, planning, interiors, color or graphics) are based on a systems approach to the total concept. We know the broad scope of thinking and the individual talent that is brought to bear on each commission. It is unsurpassed. We are entering a new age of building. An age in which a new set of ideas is taking hold. These ideas are not solely technological in nature: they are also philosophical. Relating first to larger questions of environmental planning and then concern for the isolated technical details.”

In parallel to his architecture practice. Russell was an artist. In 1962, San Diego & Point described Russell’s artwork as arresting, constructivist, severe, functionalist, and mainstream all in the same article. Of the second home Forester designed for the Russells, the magazine stated “the house….has a quiet elegance and air of privacy. The feeling, both inside and out, is one of discipline without rigidity, elegance without opulence.”

Russell Forester spent three decades juggling his passion and vision for fine art and architecture only to give up the latter for the former in 1976. With the aid of his second wife and architectural firm partner, Christine, Russell began his full-time career as a painter and sculptor when many of his contemporaries were retiring or at least retiring their modernist principles for safer ground. “Had it been up to him, he would have gone directly into art (rather than architecture). He liked the Bauhaus ideology of diverse disciplines,” remarked widow Christine Forester. “Had he been an artist since his 20s he may have not been as productive. Russell was often discouraged from pursuing his art. By the time he devoted himself full-time to art in his 50s, there was a sense of urgency. By this time his hand was very secure and there was little waste and few mistakes,” said Mrs. Forester.

Russell Forester’s career melding art and architecture was honored by his unusual FAIA recognition. Rather than his career of progressive building designs being honored, Mr. Forester was recognized by his AIA colleagues for his contribution to art and architecture aesthetics. Russell believed the central tenet to integrity of design was his residential client’s lifestyle. Some of his clients would later become patrons of his artwork -- filling their Forester-designed homes with Forester-designed artwork. Clients like Lloyd Russell, Danah Fayman and Bob Peterson commissioned Russell time and again.

One only has to look at the ceiling of Park Prospect Apartments to understand Russell’s fascination with repetition. Many of Mr. Forester’s commissions include rows of small round light bulbs -- these “dots, lines and light” are recurring themes in both his art and architecture. Whether using rows of light diodes, or punctuating his painting and sculpture (sometimes in steel) with a sewing machine, the linear repetition reflected this dots-in-line theme. Additionally, from his La Jolla home, Russell grew fascinated by coastal mist seen through the expansive glass walls. His art often reflects coastal mornings by painting, washing, and repainting and the use of gauze to reflect this misty feeling.

Russell’s building designs varied in material and style over the years he practiced (1948-1976) while retaining central design principles: the problems the client needed solving; and how the whole project was vastly more than the sum of its parts. Clients of Russell Forester Associates Inc. grew to expect a variety of things, central to which was his unquestionable integrity of his designs, passion and vision. During much of Mr. Forester’s career in architecture, San Diego’s mid-century design aesthetic was comprised of a “lack of homogeneity in materials and approach to reflecting the region. People continued to come to San Diego from elsewhere and clients wanted styles that reminded them of where they were from,” Mrs. Forester summarized. She continued, “He was a brilliant man, extremely talented, cut to the chase, detail oriented, never lost track of detail within context of project, and the ‘whole was definitely the sum of the details.”