An Educated Collector is Our Best Client

In business for nearly two decades, we are a well established, popular contemporary art boutique specializing in expertly chosen, blue chip prints, multiples, uniques, books, ephemera and merchandise at different price points, with a focus on the secondary market. Please click on the "Contact Us" button at the bottom of this page for questions about any work, pricing and/or to arrange to visit our showroom/gallery - located in between Manhattan's Flatiron and Chelsea Flower Districts.

Description

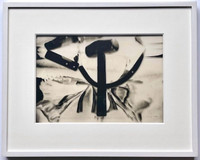

Andy Warhol

Hammer & Sickle, 1976

Acetate negative acquired directly from Chromacomp, inc. Andy Warhol's printer in the 1970s. accompanied by a letter of provenance and authenticity from the representative of Chromacomp

Frame included

Elegantly framed in a museum quality wood frame with UV plexiglass

The image can also be hung vertically, or right side down

Measurements:

Frame

15.75 inches vertical by 19.75 by 1.5 inches

Acetate

9 vertical by 13

This unique photographic negative acetate is of one of Warhol's most famous images - the Hammer & Sickle. This acetate was brought by Warhol to Eunice and Jackson Lowell, owners of Chromacomp, a fine art printing studio in New York City. During the 1970s and 1980s, Chromacomp was the premier atelier for fine art limited edition silkscreen prints; indeed, Chromacomp was the largest studio producing fine art prints in the world for artists such as Andy Warhol, Leroy Neiman, Erte, Robert Natkin, Larry Zox, David Hockney and many more. All of the plates were done by hand and in some cases photographically.

As a testament to the historical importance of this collection, we recently sold Andy Warhol's acetate of Conceptual Artist Joseph Kosuth (from this collection) -- to the artist Joseph Kosuth - himself, that of Baby Jane Holzer to the socialite herself, Jason McCoy to his family, and Tina Freeman to her representative. The Niarchos family also acquired the acetate of renowned Greek art patron and philanthropist Stavros Niarchos.

As Bob Colacello, former Editor in Chief of Interview Magazine (and right hand man to Andy Warhol) explained, "Many hands were involved in the rather mechanical silkscreening process.... but only Andy in all the years I knew him, worked on the acetates." An acetate is a photographic negative transferred to a transparency, allowing an image to be magnified and projected onto a screen. As only Andy worked on the acetates, it was the last original step prior to the silkscreening of an image, and the most important element in Warhol's creative process for silkscreening.

Famed printer Alexander Heinrici worked for Eunice & Jackson Lowell at Chromacomp and brought Andy Warhol in as an account. Shortly after, Warhol or his workers brought in several boxes of photographs, paper and acetates and asked Jackson Lowell to use his equipment to enlarge certain images or portions of images. Warhol made comments and or changes and asked the Lowells to print some editions; others were printed elsewhere. Chromacomp ended up printing a number of Warhol silkscreens and, most notably, the iconic Mick Jagger series based on the box of photographic acetates, both positives and negatives. The Lowell's allowed the printer to be named as Alexander Heinrici rather than Chromacomp, since Heinrici was the one who brought the account in. Other images were never printed by Chromacomp - they were simply being considered by Warhol. After working with Chromacomp, Warhol left the remaining acetates, including this incredibly rare and highly collectible one of HAMMER & SICKLE with Eunice and Jackson Lowell. After the Lowells closed the shop, the photographs were packed away where they remained for more than a quarter of a century. Even in his lifetime, it is well documented that Warhol recognized the unique value of the acetates, as he would often exchange them for services with silkscreen shops. It measures approximately 12 inches by 16 inches. It is unevenly cut by Andy Warhol himself, exactly as he brought it to the Lowells. Buyer will receive a hand signed letter from the Lowell family representative confirming the work's authenticity and provenance. Many of the acetates from the Chromacomp collection have already been acquired by museums, galleries, dealers and collectors around the world, and most recently a selection of acetates was exhibited, alongside the silkscreens Warhol created from them, at a museum in Naples, Italy.

Andy Warhol created his Hammer and Sickle series in 1976 after a trip to Italy where the most common graffiti in public spaces was this symbol found on Soviet flags. Under communist control, it signified the union of industrial and farm workers’ interests. In Italy, a democratic country since the end of WWII, the repeated graffiti symbol was to Warhol more pop art than political. After returning to the United States, Warhol asked his studio assistant Ronnie Cutrone to find source pictures of this symbol. The reproductions found in books were like the Soviet flag, flat in appearance, and Warhol wanted something different. Cutrone purchased a double-headed hammer and a sickle at a local hardware store and arranged and photographed the tools in many positions. Warhol used the Cutrone photographs for his silkscreened series. In 1977, these works were exhibited under the ambiguous title Still Lifes at the Castelli Gallery in New York City. Warhol disavowed any political ties to his work, though he was aware of the power of symbols and the cultural climate of the Cold War. This war between superpowers, America and the Soviet Union, from the early 1940s through the 1980s was characterized not by actual military combat but by a climate of tension and mutual perceptions of hostility between East and West, communism and capitalism, resulting in the build-up of arms, nuclear weapons, and influence peddling around the globe.

Little did I know that I would also be included on an FBI list, probably for this little art project of ours. I would find myself sneaking along the skyscrapers of the Big Apple and darting into a Red bookstore, looking over my shoulder, I’d find a couple of books and brown-bag them and nonchalantly walk out into the broad daylight. I’d return with the books, heart racing, and Andy would say, half-joking, half-serious, “Were you followed by anybody?” I would answer, “I don’t think so, but if I was, I think I’m a little too old to say I’m a college student studying the Russian Revolution.” Then he’d say, “Did you find any good ones?” I never really did. They were too flat or too graphic. The answer was to go down to Canal Street, into a hardware store, and buy a real hammer and a real sickle. Then I could shoot them, lit with long menacing shadows. And add the drama that was missing from the flat-stenciled book versions. A third dimension of rough outlines would be added and when the paintings were finished they always looked like Amusement Park rides to me. Step right up and ride The Hammer and Sickle. Only 25 cents, if you dare. Not for the weak or faint of heart. It always amused me that Andy the ultimate Capitalist, and me, the ultimate Libertarian, could be suspected of Communist activity.

Warhol’s assistant Ronnie Cutrone, Hammer and Sickle, 2002

Politics cannot be banished entirely from this image, of course. But even if Mr. Warhol is not exactly in the forefront of the international labor movement he can certainly claim the status of an experienced (he is 50 this year) and industrious workman. In these new paintings he has taken something from sculpture (Calder’s stabiles, Claes Oldenburg’s giant variants of household objects), something from architecture (from the towers of San Gimignano to the World Trade Center), and something of painting (spreading the color as a schoolboy spreads jam on his first day at summer camp) and come up with an end‐result that combines imagination with punch.

John Russell, The New York Times, January 21, 1977

Most of the people buying the Soviet paraphernalia were Americans and West Europeans. All would be sickened by the thought of wearing a swastika. None objected, however, to wearing the hammer and sickle on a T-shirt or a hat. It was a minor observation, but sometimes, it is through just such minor observations that a cultural mood is best observed. For here, the lesson could not have been clearer: while the symbol of one mass murder fills us with horror, the symbol of another mass murder makes us laugh.

Anne Applebaum, Gulag, 2003

The punk period witnessed a renaissance of tattooing—a practice which visibly asserts our ritualistic :uncivilized” past and in whose pictorial language the skull looms large. Because of a slew of ‘primitive’ and sexual associations, the tattoo is proscribed by traditional western conventions. But tattoos persist, serving to decorate, seduce, shock, scare, to declare nonconformity . . . [Warhol’s] own tattoo-like exhibitionism at the 1977 opening for his “Hammer and Sickle” paintings drew together various structures of power and pleasure: the art world/gallery system brand of capitalism; a communist emblem rendered in paintings titled Still Lifes, in which the shadow seems more real (threatening) association with leather, homosexuality, and gay rights and aesthetics; disco madness as the latest social marketplace and entertainment industry.

Gary Garrels, Discussions in Contemporary Culture, No. 2, 1989

Courtesy the Andy Warhol Museum

And below is the catalogue essay about the Hammer & Sickle painting series, from a 2013 Phillips auction which sold one of the Warhol Hammer & Sickle paintings this acetate was based on:

"I guess I’ve been influenced by everybody. But that’s good. That’s Pop.” Andy Warhol

"Everybody’s always asking me if I’m a Communist because I’ve done Mao. So now I’m doing hammers and sickles for Communism, and skulls for Fascism.” Andy Warhol

"To Andy, they were also an extension of the classic still life. For years I had been photographing still lives for Andy … he loved to experiment and update classical themes. For him, it was the best part of making art.” (R. Cutrone, ‘Hammer and Sickle’, Andy Warhol: Hammer and Sickle, exh. cat., London: Haunch of Venison, 2004, p. 5)

The present lot, executed in 1977, is a unique example of Andy Warhol’s famous Hammer and Sickle series. It was first exhibited under the title Still Lifes at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery in 1977, and is dedicated to Warhol’s friend Bob Colacello, who edited the artist’s celebrity magazine Interview for 12 years.

With Hammer and Sickle, Warhol proves once again to be the premier iconoclast of the 20th century, demonstrating his unique ability to raise ideological, historical and social issues within a single striking image. Engaging with the Communist symbol and with the classic colours of Soviet propaganda – white, black and red – Warhol deprives the hammer and sickle of its usual stern aura and transforms it into an attractive consumerist object, on a par with his earlier Coca-Cola cans and Brillo Soap Pad boxes. However, this time the subject is not a product of American capitalism, but its exact opposite, the emblem of Communist ideology. If his first controversial Brillo Soap Pad boxes were aimed at destabilising the threshold between high and low culture – undermining Clement Greenberg’s modernist separation of art and kitsch –Hammer and Sickle goes even further in conflating mass-produced imagery with propaganda. To Warhol, both the Brillo Soap Pad boxes and the hammer and sickle are nothing more than items made to sell: whether an object or an idea, it makes no difference.

First adopted by the Red Army and later incorporated into the Soviet Union’s national flag, the crossed hammer and sickle were meant to symbolise unity between industrial and agricultural labourers working together for the state. For his Hammer and Sickle series, Warhol dismantled this Communist icon into its components, arranging the tools into different compositions which were then photographed by his assistant Ronnie Cutrone. Inspired by Italian hammer and sickle graffiti seen during a trip to Naples, Warhol had originally asked Cutrone to track down images of the symbol in local bookstores. But the book images proved to be, in his words, too flat or too graphic, as Cutrone recalls: “The answer was to go down to Canal Street, into a hardware store, and buy a real hammer and sickle. Then I could shoot them, lit with long, menacing shadows, and add the drama that was missing from the flat-stencilled book versions… It always amused me that Andy, the ultimate Capitalist, and me, the ultimate Libertarian, could be suspected of Communist activity” (Hammer and Sickle, exh. cat. , New York, C&M Arts, 2002). The result was a large body of work – comprising paint and silkscreen on canvas, drawings and collages – in which the artist experimented with different solutions, just as if moving objects in an ordinary still life composition.

If considering Hammer and Sickle as a contemporary version of the typical 18thcentury still life genre, the present work becomes a memento mori, a reminder of the horrors of war and dictatorships. Although the same may be said for Warhol’s Skull series – and perhaps more generally for his Guns and Knives – the artist has here approached Communist iconography with a slightly greater sense of irony. A closer look at the handle of the sickle reveals the words “Champion no. 15 by True Temper”, the logo of the American manufacturer. Is Warhol mocking the American liberal market, or communism? Or both? The difference between capitalism and communism, between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, is irretrievably blurred. Warhol demotes the hammer and the sickle to mere objects and, with his knowing eye, transforms them still further into strikingly beautiful abstract images.