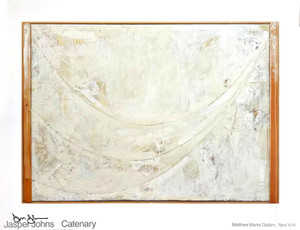

Fool's House, 1972

Fool's House (Field 154 and Gemini G.E.L. 348), 1972

10 color lithograph on Angoumois à la Main handmade paper on a single lithographic stone with an aluminum etching plate

Pencil signed and numbered from the limited edition of 67; bears printer and publisher's blind stamp (there were nine artists proofs)

Printed and published by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, with master printers Serge Lozingot and Kenneth Tyler, with the blind stamp lower right

Catalogue Raisonne Ref: Field 154 and Gemini G.E.L. 348

Provenance: From the collection of renowned art dealers Mark and Sandy Keilly of Dayton, Ohio

Another example was recently exhibited at the Parrish Art Museum in New York. This work is seldom seen on the market as so many examples are already in museum and institutional collections.

"Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it." - Jasper Johns

"Fool's House" is one of the most admired and discussed Jasper Johns prints to emerge from the 1970s. It was based upon his eponymous 1962 painting, which was part of the Castelli Collection and subsequently on long term loan to the Walker Art Center. (The original painting is 3-D as it features a real old broom with bent bristles mounted on a canvas with gray oil paint and stenciling behind it.)

The author of EPPH ("Every Painter Paints Himself: Art Masterpieces Explained") writes of the original 1962 "Fool's House" painting: "The household broom has clearly "painted" a large part of its own canvas as the arc of its brush-stroke, visible on either side of its bristles, makes clear. It is Johns' "paintbrush" even though labeled "broom" in the artist's handwriting near the bottom of its shaft. Below it too are other studio objects - a towel, stretcher and cup - all similarly labeled with arrows pointing to the corresponding object. The labels have generated much discussion about the use of names in art.."

The reference in "Fool's House" to Duchamp and the concept of the "ready made" is apparent, as here Johns takes the household broom, hangs it in the artist's studio and assigns it a different purpose altogether - one it has already partially fulfilled. (Works like the present one would cause some people to refer to Johns as a Neo-Dadaist, because it bridges the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. There's also a nod to Surrealism in the composition, with the text labels near the objects recalling Magritte's 1930 "Ceci N'es Pas Une Pipe.")

The present work (and of course the original painting) is also explicitly autobiographical, as the "Fool's House" references the artist's studio, where he can commandeer any ordinary household object - like a broom - and, literally and figuratively, incorporate it into the artmaking process. There's also a bit of self-deprecating existential angst, as the artist's paintbrush is replaced by an object used to sweep up the trash, and his studio is a "Fool's House" - because, perhaps, only a fool would be in this line of work. (Remember, the year before Johns' "Fool's House" painting, he created an ironic and cynical send-up of art critics entitled "The Critic Sees" - featuring two myopic eyes.) There is also, paradoxically, a bit of secret swagger in "Fool's House", because Johns might have anticipated that his broom, just like Duchamp's urinal, would be destined to become a masterpiece.

Perhaps the original 1962 painting this work is based upon is a hat tip to an inside art world joke about Jasper Johns' legendary dealer, Leo Castelli, made two years earlier. Jasper Johns is quoted saying, “Somebody told me that Bill de Kooning said that you could give that son-of-a-bitch (Leo Castelli) two beer cans and he could sell them. I thought, what a wonderful idea for a sculpture.” (“Jasper Johns” by Richard Francis, Abbeville Press). Hence Jasper Johns two Ballantine Ale Cans (made in 1960), made as a dare, which Castelli, of course, promptly sold.

The original 1962 painting of "Fool's House" was a classic example of art about art; A decade later, Jasper Johns' 1972 lithograph is also art about art that is about art - as it re-visits the artist's earlier 3-D painting and translates it into a different medium - a 2D graphic work on paper. While much was changed during the translation of the work into an editioned lithograph, the central composition is preserved, featuring the broom hanging from a hook, and a coffee cup hanging beyond the bounds of the 'canvas' - but in the lithograph, the cup dangles beyond the framed area of the print and onto its margins.

"Fool's House" is a coveted Jasper Johns graphic work that is increasingly scarce as so many other examples are already in the permanent collections of major public and private institutions.

This work has been elegantly floated and framed in a museum quality wood frame under UV plexiglass.

Measurements:

Framed

48 inches (vertical) by 44 inches (horizontal) by 3 inches

Artwork:

43 inches (vertical) x 29.25 inches (horizontal)

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” 2022, Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA & Whitney Museum of Art, NY (Fool's House, Black State)

"Jasper Johns: A Print Retrospective" May 19, 1986–August 19, 1986, the Museum of Modern Art, New York (another example)

Heyward Gallery, London, 1978 (another edition)

among many other exhibitions

Jasper Johns Biography:

Jasper Johns was born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, and raised in South Carolina. He began drawing as a young child, and from the age of five knew he wanted to be an artist. For three semesters he attended the University of South Carolina at Columbia, where his art teachers urged him to move to New York, which he did in late 1948. There he saw numerous exhibitions and attended the Parsons School of Design for a semester. After serving two years in the army during the Korean War, stationed in South Carolina and Sendai, Japan, he returned to New York in 1953. He soon became friends with the artist Robert Rauschenberg (born 1925), also a Southerner, and with the composer John Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham.

Together with Rauschenberg and several Abstract Expressionist painters of the previous generation, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman, Johns is one of the most significant and influential American painters of the twentieth century. He also ranks with Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, Munch, and Picasso as one of the greatest printmakers of any era. In addition, he makes many drawings—unique works on paper, usually based on a painting he has previously painted—and he has created an unusual body of sculptural objects.

Johns’ early mature work, of the mid- to late 1950s, invented a new style that helped to engender a number of subsequent art movements, among them Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual Art. The new style has usually been understood to be coolly antithetical to the expressionistic gestural abstraction of the previous generation. This is partly because, while Johns’ painting extended the allover compositional techniques of Abstract Expressionism, his use of these techniques stresses conscious control rather than spontaneity.

Johns’ early style is perfectly exemplified by the lush reticence of the large monochrome White Flag of 1955 (

1998.329

). This painting was preceded by a red, white, and blue version, Flag (1954–55; Museum of Modern Art, New York), and followed by numerous drawings and prints of flags in various mediums, including the elegant oil on paper Flag (1957; (

1999.425

)). In 1958, Johns painted Three Flags (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), in which three canvases are superimposed on one another in what appears to be reverse perspective, projecting toward the viewer.

The American flag subject is typical of Johns’ use of quotidian imagery in the mid- to late 1950s. As he explained, the imagery derives from “things the mind already knows,” utterly familiar icons such as flags, targets, stenciled numbers, ale cans, and, slightly later, maps of the U.S.

It has been suggested that the American flag in Johns’ work is an autobiographical reference, because a military hero after whom he was named, Sergeant William Jasper, raised the flag in a brave action during the Revolutionary War. Because a flag is a flat object, it may signify flatness or the relative lack of depth in much modernist painting. The flag may of course function as an emblem of the United States and may in turn connote American art, Senator Joseph McCarthy, or the Vietnam War, depending on the date of Johns’ use of the image, the date of the viewer’s experience of it, or the nationality of the viewer. Or the flag may connote none of these things. In Johns’ later work, for example The Seasons, a set of intaglio prints made in 1987 (

1999.407a–d

), it seems inescapably to refer to his own art. In other words, the meaning of the flag in Johns’ art suggests the extent to which the “meaning” of this subject matter may be fluid and open to continual reinterpretation.

As Johns became well known—and perhaps as he realized his audience could be relied upon to study his new work—his subjects with a demonstrable prior existence expanded. In addition to popular icons, Johns chose images that he identified in interviews as things he had seen—for example, a pattern of flagstones he glimpsed on a wall while driving. Still later, the “things the mind already knows” became details from famous works of art, such as the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald (1475/80–1528), which Johns began to trace onto his work in 1981. Throughout his career, Johns has included in most of his art certain marks and shapes that clearly display their derivation from factual, unimagined things in the world, including handprints and footprints, casts of parts of the body, or stamps made from objects found in his studio, such as the rim of a tin can.

-Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art